Pittsburgh Post-Gazette – Which of your senses would you give up first? Granted, the five enhance each other. But taste — that would be first to go, right? Then feeling — even with all the physical danger that would entail? Then speech?

Which leaves hearing and sight, the two that most copiously admit the world into the isolated self. Of these, I’d last relinquish sight, which seems to me the most essential link with the outside world.

Yet that’s the very sense that is slipping away in “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat,” the operatic version of the famous 1985 case study by Oliver Sacks, now staged by Quantum Theatre. Granted, the loss is only partial and of a peculiar kind, but it turns out there is compensation (both medical and operatic), so it’s not as isolating as we expect.

We first meet Dr. S, a neurologist, narrating the perplexing case of Dr. P, a classical singer whose erratic behavior has alarmed (though only to a point) his wife, Mrs. P. (Using these initials matches the protocol of discussing real case histories, but in the play it also heightens the sense of mystery.)

What follows is a detective story. Dr. S soldiers on, sifting Dr. P’s behavior. Soon he realizes Dr. P misinterprets visual information from his right eye, resulting in such anomalous behavior as that in the title — which isn’t as absurd in action as it sounds in the abstract.

That’s it: that process of diagnosis is what passes for a plot in this concise 65-minute operatic puzzle. But the opera isn’t over, because Dr. S discovers that Dr. P’s and his wife’s mode of accommodation, which is to structure life by music, is satisfying, even uplifting, compensation. So the neurologist who begins by focusing on dysfunction ends by discovering what we might call supra-function.

Telling you that breaks the rule of reviewing by giving away the central spring of the plot, which amounts basically to the search for a diagnosis. You could say the hero is the doctor’s questing mind, but of course the musician is the central figure. But this isn’t a plot in any usual sense. Instead, “The Man Who” uses the exact form of expression that the narrative discovers it is about. The opera is the story of itself, of its own mode of being.

Hence the insufficiency of analysis by plot, character, setting, language and idea — the five senses of theater. “The Man Who” is all about its language, which is music. So hearing is the most essential sense for the audience, allowing enjoyment of Michael Nyman’s ravishing score.

Almost continuous song alternates with a form of recitative, spelled occasionally by narrative bridges. I’m not equipped to speak professionally about the score, but I can say it is very accessible. Often lilting, even sweet, it also has an urgency sometimes descending into ominous, occasionally jagged darkness.

As long as there is music, there is life, both in the story and onstage.

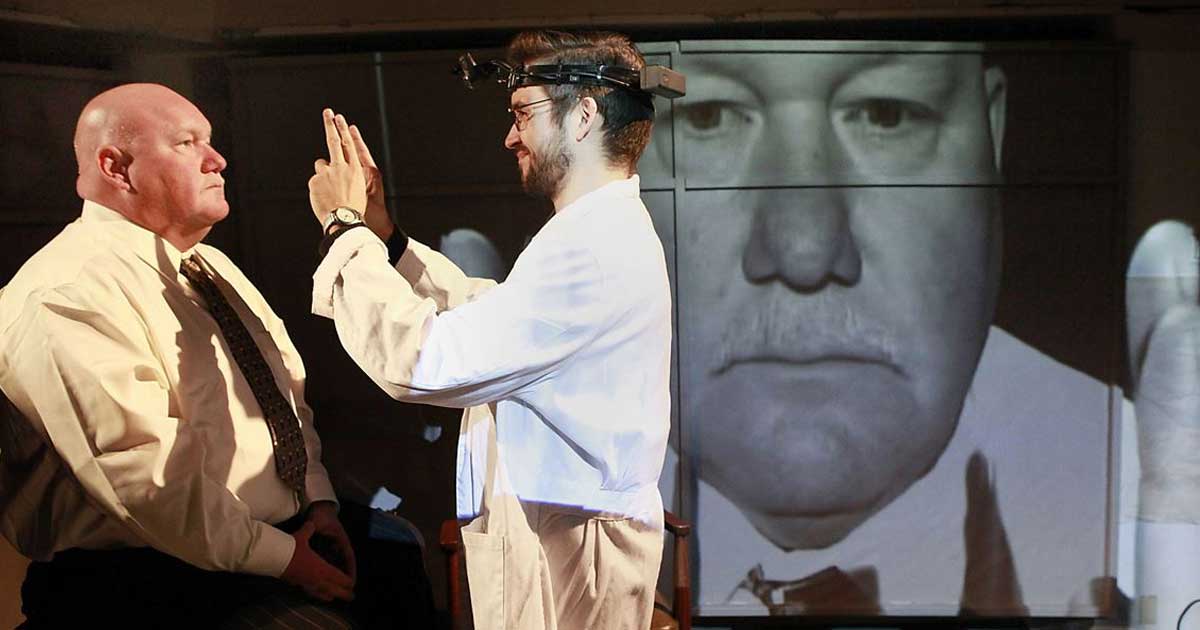

But the production also powerfully invokes the sense of sight with the projections by Joe Seamans, who has become an essential part of the Quantum artistic team. Sometimes they illustrate the text, but often they comment on it or run across it, stirring varying emotions like poetry.

Quantum artistic director Karla Boos directs, often keeping the actors static, the better to feature the music and the projected images circling behind them. Her usual musical collaborator, Andres Cladera, directs an orchestra of seven that pours forth the main riches of the brief performance.

Ian McEuen (Dr. S), Kevin Glavin (Dr. P) and Katy Williams (Mrs. P) meld score and words (often their words are projected, as well). Mr. Glavin bears the greatest weight. I found his almost-pompous befuddlement especially moving. Apparently oblivious to his circumstances, he gradually, delicately intimates his insecurity and fear.

“He had no body image,” Dr. S finally says. “He had body music.” But then, accompanied by Mr. Seamans’ Munch-like wash of discordant, muted color, Dr. S says, “But when the music stopped, so did he.”

I was left with a sense of desolation, albeit the heightened desolation that art makes almost pleasurable.